From the DukeHealth.org archives. Content may be out of date.

From the DukeHealth.org archives. Content may be out of date.

Painless Alternative to Mammogram in the Works

Creates Better Images at Lower Radiation Doses

Martin Tornai, PhD, in front of his new breast imaging system.

A new approach to breast imaging being developed at Duke requires no painful breast compression and takes more sensitive, higher-quality images with lower doses of radiation than conventional mammograms. With FDA approval, it could one day replace mammography.

Clear Differences Between Tumors, Benign Masses

The genesis for a hands-off breast-imaging advance started with a few simple questions. Duke radiology researcher Martin Tornai, PhD, asked, “Why should a patient undergo an uncomfortable procedure? How can we do this three-dimensionally? How can we do it with lower radiation?”

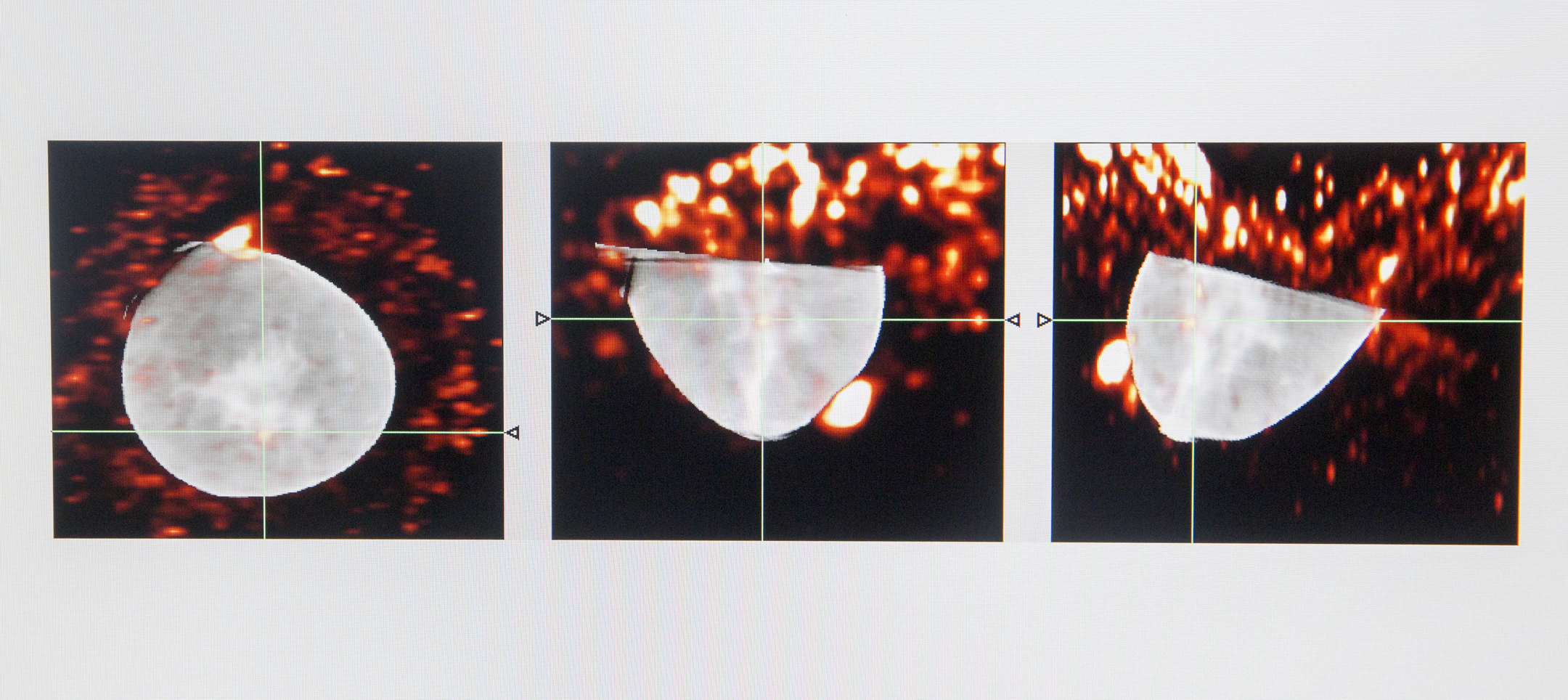

Tornai combined CT, which creates high-quality 3D images, with SPECT, a 3D nuclear imaging scan that identifies tumors illuminated by an injected radioactive molecule. CT shows the structure of organs, while SPECT shows how organs work, he explained.

Together, the 3D images display clear differences between ragged cancerous tumors and smoother, benign masses. “Because our images have a high level of conspicuity,” he says, referring to their ability to distinguish things, “we can see if a lesion has what looks to be the legs of a crab, which is what ‘cancer’ is named for. We can also determine what’s going on with the metabolism of that suspicious area.” This helps doctors understand how quickly the cancer is growing or spreading to nearby areas.

That level of definition cannot be viewed on a regular X-ray mammogram, although it can, to some degree, with the newest generation of mammography -- tomosynthesis -- which is not-quite CT with X-ray. Tomosynthesis still requires breast compression.

One woman told Tornai, “'this is so comfortable I don’t want to get up.’ That was gratifying,” he said.

No Breast Compression, Less Radiation

While better images are important, the new scan’s lack of compression could be a game changer. Some women avoid getting a mammogram because they feel uncomfortable having their breasts handled and squished painfully between two plates.

Tornai’s equipment requires no breast compression or handling at all.

After lying facedown on a special table, a woman positions her free hanging breast through a hole and into the imaging area. The two imaging systems circle and create 360-degree images of the entire breast and chest wall. Following a scan that was performed as part of research on the device, one woman told Tornai, "'this is so comfortable I don’t want to get up.’ That was gratifying,” he said.

Tornai’s group has also worked extensively on the x-rays themselves; the total radiation dose for a full 3D breast CT is now lower than for a mammogram. Tomosynthesis, in its current FDA-approved use, requires more radiation.

More Breast Images from Different Angles

Current mammography creates a single, 2-D image. Tissue at the top, the middle, and the bottom of the breast all overlap onto this one image, like a sandwich, Tornai explained. However, the parts of the stack are not distinguishable from each other.

“3D mammography,” a term often used to describe tomosynthesis, creates a series of imaging slices at different levels of the breast. This makes it possible to better distinguish some parts of the image stack.

Neither device creates the “isotropic” images achieved with CT/SPECT. Isotropic refers to the ability to see identical parts of the stack from every direction without losing any resolution or conspicuity. This enables radiologists to look behind and around objects -- a breast implant for example -- and gives them a better understanding of what is going on in the 3D space.

“You would never see that on a normal mammogram,” Tornai said. “You would have to put the patient and her breast in awkward positions to be able to take numerous pictures from different angles.”

Promising Results, Lower Call Back Rates

A private company licensed Tornai's patent and is developing the device. It is currently seeking additional funding to move it to the next phase of testing. If, as expected, it receives FDA approval, Tornai believes it could one day replace mammography.

“The current results have been good,” he said, speaking to the device’s ability to identify a cancerous mass. “We can potentially reduce the recall rate [meaning women called back for more scans] by around 70 to 75 percent,” Tornai said. And that may reduce the number of women who need a breast biopsy.