A Short Wait on the Transplant List, Thanks to Duke Health and the HOPE Act

James Golden in his home in Durham, NC.

James Golden, who is HIV-positive, was housebound with a dangerous neurological condition caused by liver disease when it became clear that he needed a liver transplant. He received the transplant at Duke University Hospital shortly after being added to the waitlist, thanks to its status as one of the few centers nationally approved to use organs from HIV+ donors through the HOPE (HIV Organ Policy Equity) Act. “He went from a situation where he was regularly getting confused and life-threateningly unwell, to being a very clear, thoughtful, and a delightfully engaging individual who's getting back into the swing of life,” said Golden’s doctor, Duke infectious disease specialist Cameron R. Wolfe, MBBS.

The Rocky Road to Transplant

About a decade ago, Durham resident James Golden, 56, was shocked to learn that he had developed cirrhosis, a late stage of liver disease in which healthy tissue is replaced by scar tissue, preventing the liver from functioning properly. “My platelets kept dropping, but my liver function numbers were normal, and I wasn't experiencing any symptoms,” said Golden.

But soon, fatigue sent in. More troublingly, Golden began to experience episodes of hepatic encephalopathy (HE), a neurological condition caused by severe liver damage in which the liver can no longer remove toxins such as ammonia from the blood. The toxins accumulate in the blood and affect the brain, leading to confusion and physical and cognitive impairment. The treatment to prevent relapses of HE is to drink a special liquid to flush the ammonia out of the body, and Golden was using so much of it that he constantly had to use the bathroom and couldn’t leave the house. Golden lived with intermittent bouts of HE for about two years, during which he lost one job and couldn’t get through the training program for another.

“My last episode was really severe,” said Golden. “I had a seizure, and EMS had to roll me up in a blanket to get me into the ambulance. It was scary. I remember waking up in the ER and my tongue was so swollen that I couldn’t talk.”

It was time to think about a liver transplant. Golden’s HIV doctor sent him to the transplant clinic at the hospital where he received his care. “On my very first visit, the doctor told me that they probably wouldn’t do the transplant because I had portal hypertension, a byproduct of my cirrhosis,” he said. But his HIV doctor told him that Duke was doing transplants with HIV-positive people, and referred him to Dr Wolfe.

Hope From the HOPE Act

“As soon as I talked to Cameron, he was like, ‘Oh yeah, come over. You’re a perfect candidate. Your chances of getting a liver are really good,’” said Golden.

“[Golden] not only needed the liver and was well enough to tolerate the surgery but also had a history of really well-controlled HIV. That not only suggested that it would be safe, but that he was likely to continue to do well on the other side,” explained Dr. Wolfe. “He also had a good support system, with lots of friends around him, which is so important after transplant.”

Because of his HIV status, Golden was placed on two waiting lists for a donor organ: the regular list maintained by United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), and a newer list made possible by the HOPE (HIV Organ Policy Equity) Act. Signed into law on November 2013, the HOPE Act allows organ transfers from HIV-positive donors to HIV-positive recipients, which had been previously prohibited.

To perform these transplants, centers must have significant experience in bringing HIV-positive candidates through the transplant process. So far, only a small number have made the cut. Duke is the only transplant center in the country that has been approved to offer transplants through the HOPE Act for lungs, hearts, livers, or kidneys, both living and deceased.

Dr. Wolfe noted that being on the HOPE Act list is a real advantage. “For liver transplants, you’re looking at a national HIV-positive list of typically less than 10 people as opposed to somewhere around a thousand for HIV-negative patients,” he said. “The same competitive advantage exists for patients on the kidney waitlist. We had a person who'd waited years on a kidney waiting list and was transplanted with us in a matter of a week.”

A Successful Surgery

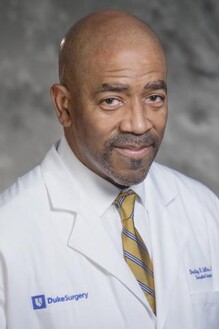

Three weeks after Golden was approved for transplant, he got a call that a liver from an HIV-positive donor was available. He was transplanted on December 16, 2023 by Duke transplant surgeon Bradley H. Collins, MD. “It was so fast,” Golden marveled. Six days later, he went home. Today, Golden is doing well and looking forward to camping with friends in his RV.

Aside from making more organs available to more people, Dr. Wolfe noted an additional benefit to the HOPE Act. “We can now ask healthy HIV patients if they’ve ever thought about being on the organ donor registry, which is quite empowering for them. Hopefully both of these things help diminish the stigma a little bit,” he said.

Golden agrees. “I'm a firm believer in this HOPE Act," he said "If we have HIV-positive people who could donate, why can’t they donate to at least a group of people who can accept their liver? Don't just throw those things away.”