Cochlear Implant Boosts Teen’s Hearing and Speech Skills

Andy Torres works with speech pathologist Megan Katz at the Duke Speech Pathology and Audiology Clinic.

Andy Torres was a toddler when he was diagnosed with moderate to severe hearing loss. Hearing aids and speech therapy helped Andy learn to communicate, but his hearing and speech progress plateaued as he approached adolescence. After receiving a cochlear implant -- a surgically implanted device that delivers sound by directly stimulating the auditory nerve -- at Duke Health, Andy now hears high-frequency sounds he couldn’t hear before, he can better understand conversation, and he’s performing better in school. “Whatever we can do to improve his life, we will do it,” Andy’s dad Serguei Torres said. “That's why we said yes to the cochlear implant.”

Seeking Treatment for Hearing Loss

Andy Torres was born in Cuba in 2011. At about 15 months old, Andy started becoming less responsive when spoken to. One day, his dad purposefully banged loudly on a pan, but Andy didn’t wake up from his nap. “That’s when I realized something was wrong," Serguei Torres said.

Testing showed Andy had significant hearing loss in both ears. He was fitted with hearing aids and began regular speech therapy, which helped him develop important communication skills as he grew.

Growing Up Requires Advanced Skills

When Andy and his family moved to Durham, NC in 2017, Andy started seeing audiologists and speech therapists at Duke Health. “He had usable hearing in the low frequencies, but it steeply sloped downward in the high frequencies,” Duke audiologist Christine Holmes said. “We get the majority of our understanding of speech in the mid and high frequencies, so without that, you can hear people talking, but it's hard to understand what they're saying.”

As Andy got older, he struggled with more advanced hearing-related skills like hearing and remembering multi-step instructions; putting together words to build sentences; and executive function, meaning how the brain thinks, processes emotion, and drives behavior.

Considering a Cochlear Implant

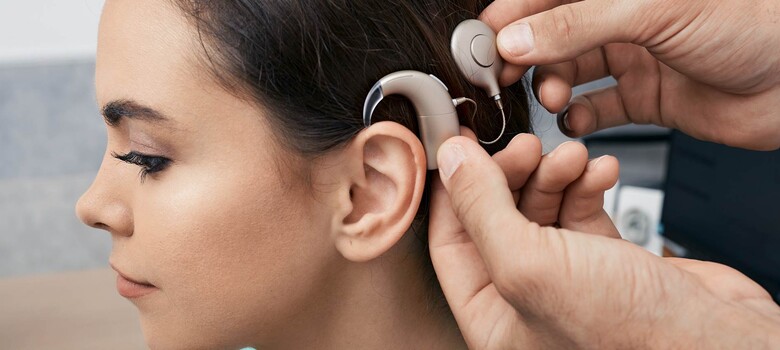

When Andy was 10 years old, Holmes recommended a cochlear implant. Unlike traditional hearing aids, cochlear implants bypass the inner ear and send electrical pulses directly to the auditory nerve. The pulses travel to the brain where they are interpreted as sound. The device requires surgery that can diminish existing hearing that is already limited. “When you insert a cochlear implant, any remaining sensory cells that are still functioning can be damaged,” Holmes said. In exchange, a cochlear implant offers the full range of hearing the wearer would not have otherwise.

Andy wanted the implant, but his parents were hesitant. Speaking to another family whose child had a cochlear implant made them feel more comfortable. “We were still scared, but we trusted the process,” Serguei Torres said.

Learning to Hear in a New Way

Andy was 11 years old when he received his cochlear implant in March 2022. Duke otologist/neurotologist Howard Francis, MD, performed the surgery. Two weeks later, after his incision was healed, Andy’s device was turned on for the first time. “It sounded like Mickey Mouse at the beginning,” Andy said. As time passed, his brain adapted to this new way of hearing and things began to sound more normal.

Andy continued speech therapy to take advantage of his new potential. “His speech became clearer,” Duke speech-language pathologist Kasey Johnson said. “His language skills started scoring within normal limits. He was hearing smaller words in sentences better. His auditory memory was getting better. It took some time because the cochlear implant really changes the way you hear, but he caught on really fast.”

Looking back, Andy and his parents are glad they took the plunge. “The proof is how he's doing now,” Serguei Torres said. “The progression in his speech is remarkable.”

When to Consider Cochlear Implantation

When hearing aids have done all they can, Holmes encourages parents to consider cochlear implantation for their children with hearing loss. “See where your child is performing compared to their normal-hearing peers. If there is a gap that is widening, it might be time to take the next step.”