8 Questions to Ask Your Doctor Before Thyroid Surgery

Duke doctors perform thyroid surgery on a patient at Duke Raleigh Hospital.

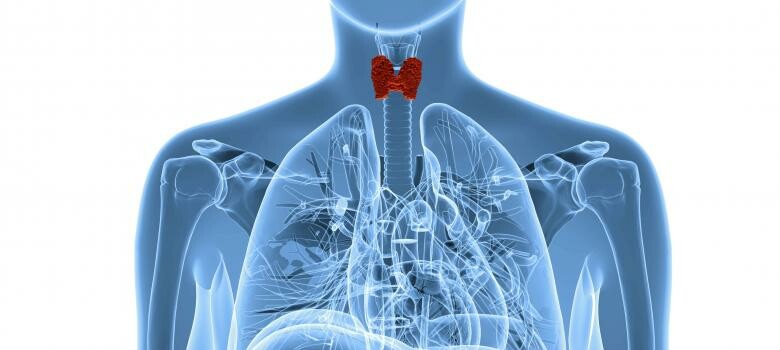

Your doctor may recommend surgery to remove part or all of your thyroid gland if it’s overactive, has grown very large, or has nodules, cysts or other growths that are—or could be—cancerous. Here are 8 essential questions to ask before you schedule thyroid surgery.

1. How much of my thyroid will be removed?

It depends on the reason for your surgery. If your thyroid is overactive (hyperthyroid from Graves’ disease or a what’s called a toxic multinodular goiter), or the whole gland is enlarged and causing symptoms—such as a feeling of pressure or difficulty talking, breathing, or swallowing—the whole thyroid should be removed in a procedure called a total thyroidectomy, said Duke endocrine surgeon Michael Stang, MD. “If only half your thyroid is enlarged and causing symptoms, but the other half is normal, then only half of the gland may be removed,” said Stang.

If your thyroid cancer is considered low-risk, your doctor may recommend removing half or all your thyroid, depending on your circumstances. “If you have an intermediate or high risk of cancer recurrence — meaning it has spread outside the thyroid—we recommend removing the whole thyroid gland,” Stang said.

Sophisticated imaging, called ultrasound neck mapping, can help your surgeon determine ahead of time how much of your thyroid and which lymph nodes, if any, need to be removed. While not in use everywhere, neck mapping is routine at Duke. “The best chance for a cure for thyroid cancer is making sure we remove all of the disease in your initial surgery,” said Hadiza S Kazaure, MD. “We don’t want to overtreat, but we also don’t want to undertreat. Knowing exactly how much surgery a patient needs is very important.”

2. What type of thyroid surgery am I a candidate for?

Conventional thyroid surgery is done through an incision in the front of the neck. The size of the incision depends on factors such as how large your thyroid is and whether the surgeon needs to remove lymph nodes.

If your thyroid isn’t very large, and no lymph nodes are involved, you may be a candidate for minimal-access surgery. Said Kazaure, “We use a small incision typically in a neck crease, which minimizes the scar.” The incision is directly over the thyroid, making it easy for the surgeon to access the gland.

Another approach is robot-assisted surgery. The surgeon controls a robotic system that directs the movements of small instruments inserted into an incision under your arm. Using the system’s high-definition 3D vision technology, the surgeon guides the instruments under your skin to your thyroid, avoiding a neck scar. “Some patients are candidates for this procedure, as long as the thyroid isn’t too big,” said Stang, who has extensive experience with this technique. “However, if it’s thyroid cancer and it’s too advanced or has spread beyond the thyroid, then a conventional surgical approach is best.”

3. How many thyroid surgeries do you each year?

Duke research shows that surgeons who perform 25 or more thyroid surgeries a year have the lowest complication rates. Yet about half of all U.S. surgeons who do thyroid surgeries do as little as just one a year. “If a doctor does fewer than 25 thyroid surgeries a year on average, their patients have about a 50% increase in the likelihood of having a complication,” said Stang.

4. What is your complication rate?

The answer you want to hear is the surgeon’s own complication rate for the procedure—not the average 1% reported in the medical literature. “If the surgeon only does two thyroid surgeries a year and one patient had a problem, that makes it a 50% risk,” said Kazuare. Don’t be shy about asking for this information. Said Stang, “It’s the ethical responsibility of the surgeon to report the truth and to know their own data.”

Duke clinical outcomes are independently reported to the National Collaborative Endocrine Quality Improvement Program (CESQIP). It tracks and compares outcomes from the best endocrine surgery centers in the country. Few surgeons have access to this kind of real-time data regarding their specific outcomes and risk of complications.

5. How will you partner with the rest of my medical team?

After surgery, you’ll likely need monitoring of your thyroid hormone levels and, in the case of thyroid cancer, follow-up treatment, and testing. “You want to know that the people taking care of different aspects of your thyroid disease or thyroid cancer are working together and communicating as a team,” said Stang. “Our team, which includes your surgeon, your endocrinologist, pathologists, and radiologists, meet to discuss the complexity of each case individually. Together, we arrive at a consensus for the best treatment."

6. Does this treatment follow published guidelines?

Professional associations for medical specialties—such as the American Thyroid Association (ATA)—regularly review the latest research and set treatment guidelines for achieving the best patient outcomes. “You want to be sure your surgeon is familiar with and using the published guidelines,” said Stang. You can check the guidelines on the ATA website.

7. What are the risks of thyroid surgery?

All surgery brings risks for complications like bleeding and infection. Thyroid surgery can also involve risks for impairment to vocal cord nerves, which could cause hoarseness, and impairment to your parathyroid glands, which are located behind and very close to your thyroid and regulate your body’s calcium levels.

8. Will I Have a Scar?

If you have open or minimal-access surgery, you will have a scar on your neck. Your surgeon may be able to make the incision in a natural crease, where it will blend in. If your surgeon performs robot-assisted surgery from an incision in your armpit, your scar will be under your arm.

Scarring depends on both surgical technique and your unique healing. There are techniques that can make a scar less visible. Ask your surgeon what technique he or she will use to close the incision.

While the length of your scar will depend on the size of your incision, Kazaure said, “I tell patients I’m going to make their incision as small as possible but as long as necessary, so that we find that balance between cosmetic result and safety.”